Salomé may be the strangest thing Oscar Wilde wrote. It's definitely one of the strangest plays I've read and it's also one of my favourites.

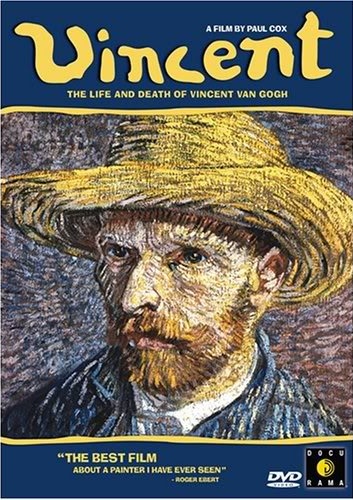

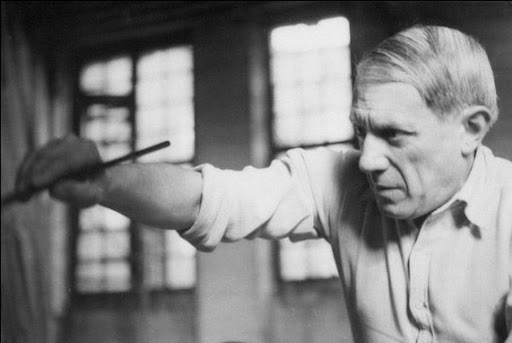

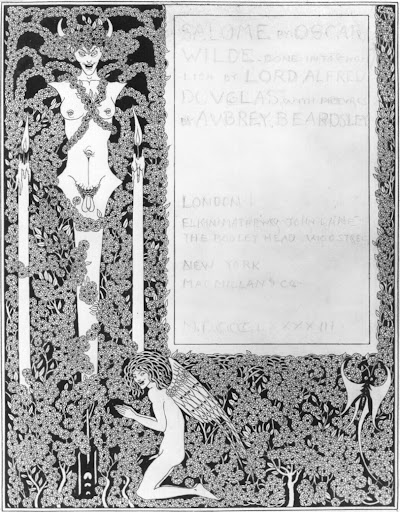

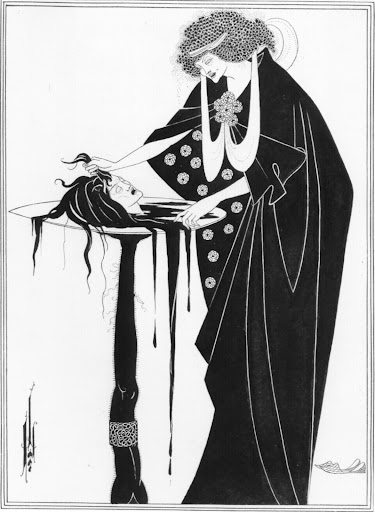

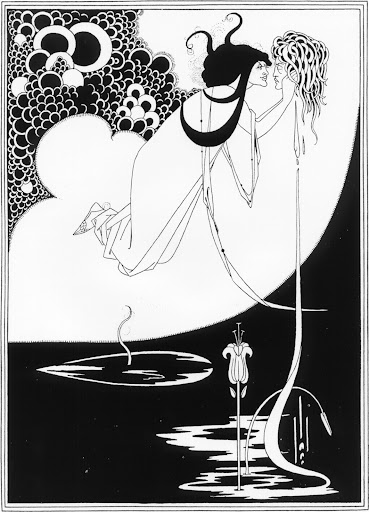

The book this was scanned from didn't have the original Aubrey Beardsley illustrations, so I tracked them down and included them with the file.

From Robert Ross:

Salomé has made the author’s name a household word wherever the English language is not spoken. Few plays have such a peculiar history. Before tracing briefly the vicissitudes of a work that has been more execrated than even its author, I venture to repeat the corrections which I communicated to the Morning Post when the opera of Dr. Strauss was produced in a mutilated verson at Covent Garden in December, 1910. That such reiteration is necessary is illustrated by the circumstance that a musical critic in the Academy of December 17th, 1910, wrote of Wilde’s “imaginative verses” apropos of Salomé — a strange comment on the honesty of musical criticism. Salomé is in prose, not in verse.

Salomé was not written for Madame Sarah Bernhardt. It was not written with any idea of stage representation. Wilde did not write the play in English, nor afterwards re-write it in French, because he “could not get it acted in English” as stated by Mr. G. K. Chesterton on the authority, presumably, of Chambers’s Encyclopaedia or some other such source of that writer’s culture. It was not offered to any English manager. In no scene of Wilde’s play does Salomé dance round the head of the Baptist, as she is represented in music-hall turns. The name “John” does not occur either in the French or German text. Critics speak contemptuously of “Wilde’s libretto adapted for the opera.” Except for the performance at Covent Garden which was permitted only on conditions of mutilation, there has been no adaptation. Certain passages were omitted by Dr. Strauss because the play (which is in one act) would be too long without these cuts. Wilde’s actual words in Madame Hedwig Lachmann’s admirable translation are sung. The words have not been transfigured into ordinary operatic nonsense to suit the score. When the opera is given in French, however, the text used is not Wilde’s French original, but a French translation fitted to the score from the German.

Salomé was written by Oscar Wilde at Torquay in the winter of 1891–2. The initial idea of treating the subject came to him some time previously, after seeing in Paris a well-known series of Gustave Moreau’s pictures inspired by the same theme. A good deal has been made of his debt to Flaubert’s tale of Herodias. Apart from the Hebrew name of “Iokanaan” for the Baptist the debt is slight, when we consider what both writers owe to Scripture. On Flaubert’s Tentation de Saint Antoine Wilde has indeed drawn considerably for his Oriental motives ; not more, in justice it must be added, than another well-known dramatist drew on Plutarch, Bandello, and other predecessors. The simple syntax was, of course, imitated directly from Maeterlinck, who has returned the compliment by adapting to some extent other features from Salomé in his recent play Mary Magdalene, a point observed by the continental critics. Our old friend Ollendorff, too, is irresistibly recalled by reading Wilde’s French; as he is indeed by all of M. Maeterlinck’s early plays. A famous sentence in one of John Bright’s speeches Wilde bodily transferred when he makes Iokanaan say, “J’entends dans le palais le battement des ailes de l’ange de la mort.” Large portions of Holy Writ, too, are incorporated. One of the musical critics is particularly severe on some of the Biblical quotations from Ezekiel (spoken by Iokanaan). He finds them “typical of Wilde’s perverted imagination and tedious employment of metaphor.” To the more scholarly and truffle-nosed industry of Mr. C. L. Graves I am indebted for the discovery that Wilde probably got the idea of Salomé’s passion for Iokanaan from Heine’s Atta Troll, though it is Herodias, not her daughter, who evinces it. Before this discovery was announced in the Spectator, that too was merely a disgusting invention of Wilde, who is, of course, anathema to “the journal of blameless antecedents and growing infirmities,” as a well-known statesman said so wittily.

So much for the origins or plagiarisms of Salomé. It is well to remember also the many dramas and ballets composed by various French writers, including Massenet’s well-known opera Herodiade, composed in 1881, and performed in 1904 at Covent Garden with the title Salomé. All of these were taken directly from the story told by St. Mark or Flaubert ; nearly all of them are now forgotten. Wilde would certainly have seen one by Armand Sylvestre. Sudermann’s Johannes, from which Wilde is also accused of lifting, did not appear until 1898, several years later. Needless to say, there is no resemblance beyond that which must exist between any two plays in which John the Baptist and Herod are characters. Wilde’s confusion of Herod Antipas (Matt. xiv. 1) with Herod the Great (Matt. ii. 1) and Herod Agrippa the First (Acts xii. 23) is intentional. He follows a mediaeval convention of the mystery plays. There is no attempt at accurate historical reconstruction.

Madame Bernhardt, who in 1892 leased the Palace Theatre for a not very successful London season, had known Wilde from his earliest days. She has recorded her first meeting with him at Dover. He was constantly at the theatres where she was acting in London. She happened one day to say that she wished Wilde would write a play for her. One of his dramas had already appeared with success. He replied in jest that he had done so. Ignorant, or forgetful, of the English law prohibiting the introduction of Scriptural characters on the stage, she insisted on seeing the manuscript, decided on immediate production, and started rehearsals. On the usual application being made to the Censor for a licence it was refused. This is the only accurate information about the play ever vouchsafed in the Press when the subject of the opera is under discussion. Wilde immediately announced that he would change his nationality and become a Frenchman, a threat which in spired Mr. Bernard Partridge with a delightful caricature of the author as a conscript in the French Army (Punch, July 9th, 1892).

The following year, 1893, the text was passed for press, the late M. Marcel Schwob told me, by himself. He made only two corrections, he in formed me, because he was afraid of spoiling the individuality of Wilde’s manner and style by transmuting them into more academic forms and phrases. I have learned since, however, that Mr, Stuart Merrill, the well-known French–American writer, a great friend of Wilde, was also consulted, and that M. Adolph Rette and M. Pierre Louys (to whom the play is dedicated) claim to have made revisions. But no one who knew Oscar Wilde with any degree of intimacy would admit that Salomé, whatever its faults or merits or de rivations, owed anything considerable to the invention or talents of others. Emerson said that “no great men are original.” However this may be, Salomé is more characteristic and typical of Wilde’s imperfect genius, with the possible exception of The Importance of Being Earnest, than anything else he ever wrote. The sculptor must get his clay or bronze, his marble and his motives from somewhere, just as the painter his pigment and models. How much more does this apply to the dramatist? The play was published in French simultaneously by Messrs. Elkin Mathews and John Lane in London and by the Librairie de l’Art Independant in Paris in 1893. It was assailed by nearly the whole Press. But there was one exception : that of Mr. William Archer in Black and White. Now that Salomé has become part of the European dramatic repertoire, though so often consigned to oblivion by two generations of dramatic critics and though the fungoid musical critics have spawned all over it, Mr. Archer’s words have a special and peculiar interest :

“There is at least as much musical as pictorial quality in Salomé. It is by methods borrowed from music that Mr. Wilde, without sacrificing its suppleness, imparts to his prose the firm texture, so to speak, of verse. Borrowed from music may I conjecture through the mediation of Maeterlinck. . . . There is far more depth and body in Mr. Wilde’s work than in Maeterlinck’s. His characters are men and women, not filmy shapes of mist and moonshine. His properties are far more various and less conventional. His . . . palette is infinitely richer. Maeterlinck paints in washes of water-colour. Mr. Wilde attains to depth and brilliancy of oils. Salomé has all the qualities of a great historical picture, pedantry and conventionality excepted.” Black and White, March llth, 1893.

I do not know that Mr. Archer liked the play particularly or that he likes it now, but at all events he had the foresight and the knowledge to realise that here was no piece of trifling to be dismissed with contempt or assailed with obloquy. Mr. Archer has fortunately lived to see a good many of his judgments justified, and beyond emphasising his interesting anticipation of the eventual place Salomé was to occupy in musical composition, I need pay no further tribute to the brilliant perception of an honoured contemporary. The Times, while depreciating the drama, gave its author credit for a tour de force in being capable of writing a French play for Madame Bernhardt, and this drew from Wilde the following letter, which appeared in the Times on March 2nd, 1893:

“SIR, My attention has been drawn to a review of Salomé which was published in your columns last week. The opinions of English critics on a French work of mine have, of course, little, if any, interest for me. I write simply to ask you to allow me to correct a misstatement that appears in the review in question.

“The fact that the greatest tragic actress of any stage now living saw in my play such beauty that she was anxious to produce it, to take herself the part of the heroine, to lend to the entire poem the glamour of her personality and to my prose the music of her flute-like voice this was naturally, and always will be, a source of pride and pleasure to me, and I look forward with delight to seeing Mme. Bernhardt present my play in Paris, that vivid centre of art, where religious dramas are often performed. But my play was in no sense of the words written for this great actress. I have never written a play for any actor or actress, nor shall I ever do so. Such work is for the artisan in literature not for the artist.“I Remain, Sir, Your Obedient Servant,“OSCAR WILDE.”

The Censor was commended by all the other reviewers and dramatic critics. Never has that official been so popular.

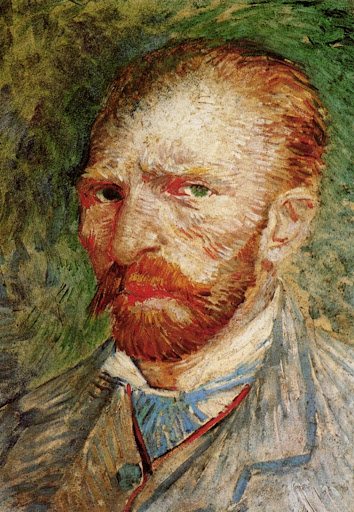

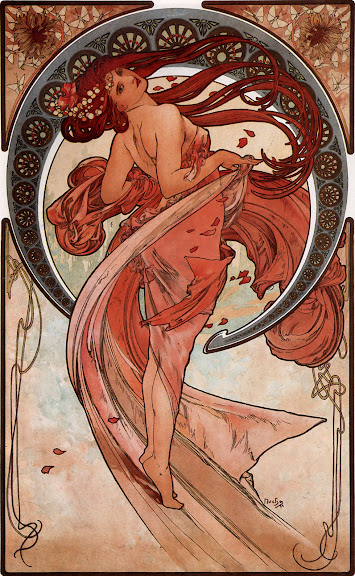

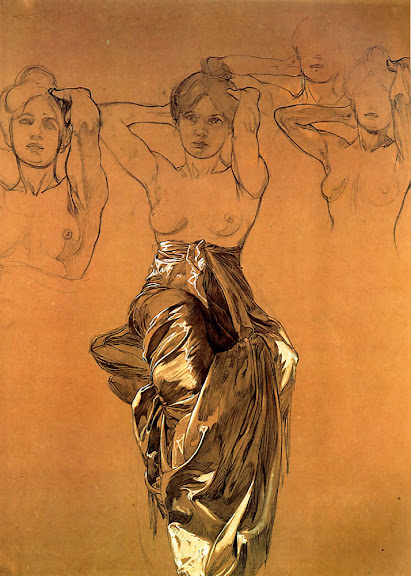

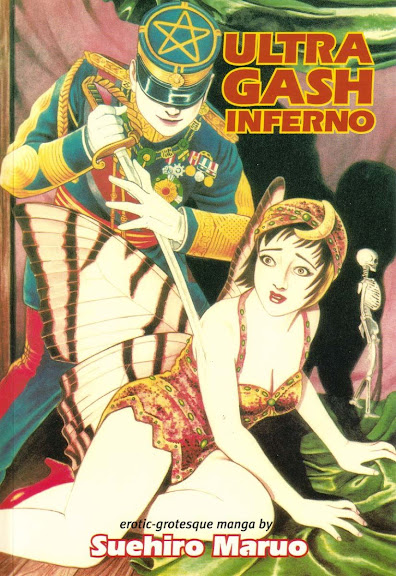

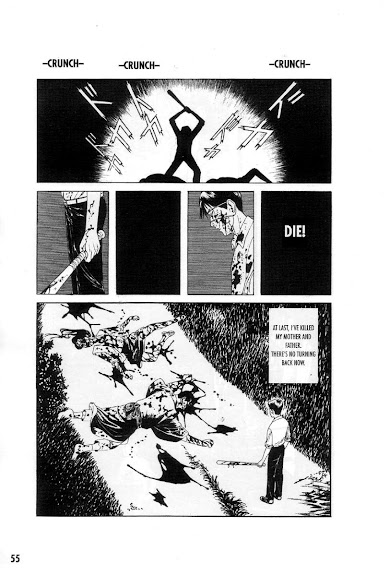

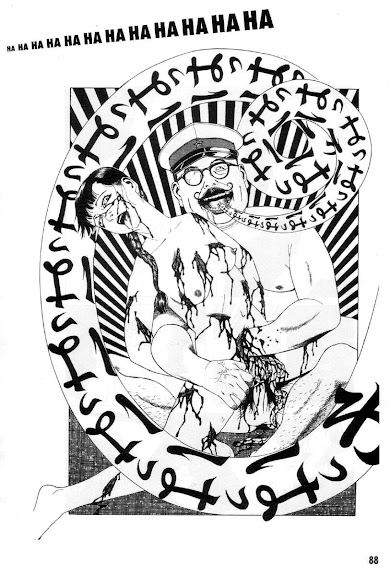

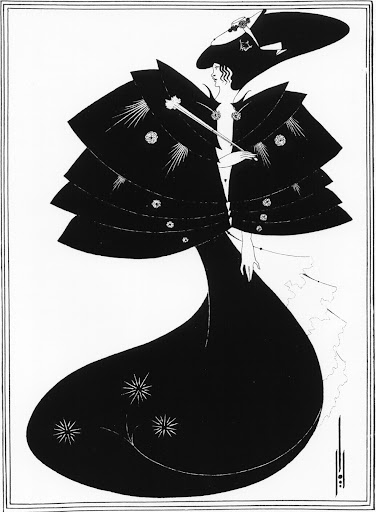

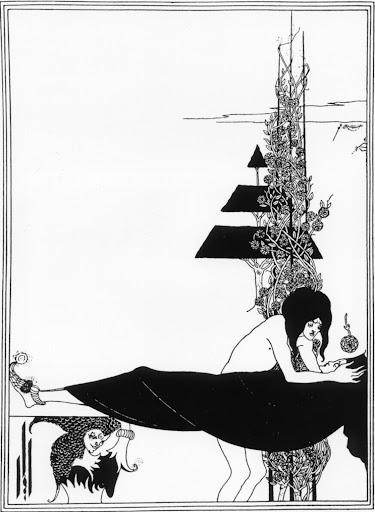

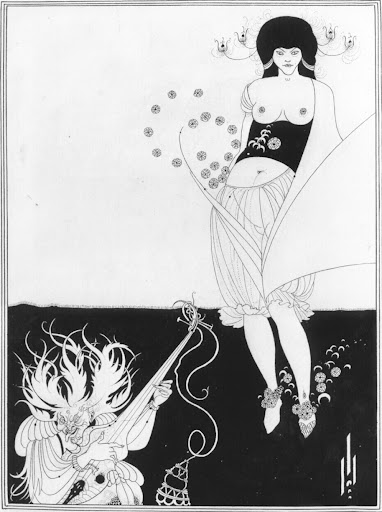

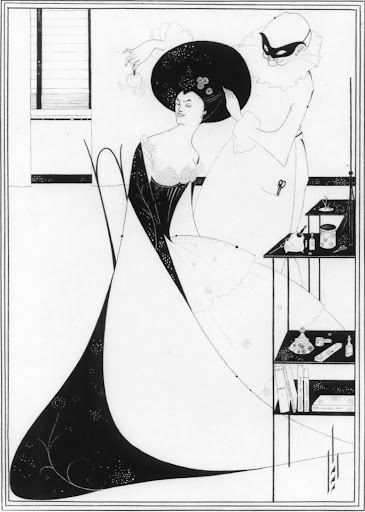

In 1894 Messrs. Mathews and Lane issued an English translation of Salomé by Lord Alfred Douglas. The illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley which it contained were received with even greater disfavour by reviewers and art critics. A few of the latter, the late P. G. Hamerton and Mr. Joseph Pennell among others, realised, however, that a new artistic personality had asserted itself, and that the draughtsman was, if anything, hostile to the work he professed to embellish. Heir Miergraefe, the German critic, has fallen into the error of supposing that Beardsley’s designs were the typical pictorial expression of widespread admiration for Wilde’s writings. They are, of course, a mordant, though decorative, satire on the play. Excellent caricatures of Wilde may be seen in the frontispiece entitled “The Woman in the Moon” (Plate 1) and in “Enter Herodias” (Plate 9). The colophon is a real masterpiece and a witty criticism of the play as well. The impression the drawings have produced, not so much in England but in Europe, may be gauged by reference to the work of the same German critic, who in his universal survey of modern art allows only three artists of the English School separate chapters to themselves the three being William Morris, Whistler, and Beardsley.

By connoisseurs of Beardsley’s work the Salomé set of drawings is regarded as the highest achievement of a peculiar talent. In England, from constant reproductions and exhibition, they were more familiar to the public than the text of the play, until the revived interest in Wilde’s writings.

And here I may warn collectors against the numerous forgeries of the originals which are continually offered in the English and American markets. Of the sixteen drawings fourteen are still in the possession of Mr. John Lane. One (“Toilette,” Plate No. 12) is in the possession of the present writer, and “Enter Herodias” has recently passed from the collection of Mr. Herbert Pollit to that of Mr. W. D. Hutchinson. There is a coloured design of Salom6, one of Beardsley’s very few coloured drawings, belonging to Miss Doulton. This was never intended as an illustration for the play in published form, but on being shown to Mr. Lane suggested to him the idea of commissioning Beardsley to illustrate the English version of the play (Marillier, “Early Work of Aubrey Beardsley,” page 23). All others are spurious.

In 1896, when Wilde was still incarcerated at Reading, M. Lugne–Poe, the poet and actor, produced Salomé at the Theatre de l’OEuvre in Paris. It was coldly received. But the author, who heard of its production, refers pathetically to the incident in one of his letters to me from prison :

“Please say how gratified I am at the performance of my play, and have my thanks conveyed to Lugne–Poe. It is something that at a time of disgrace and shame I should still be regarded as an artist. I wish I could feel more pleasure, but I seem dead to all emotions except those of anguish and despair. However, please let Lugne–Poe know that I am sensible of the honour he has done me. He is a poet himself. Write to me in answer to this, and try and see what Lemattre, Bauer, and Sarcey said of Salomé”

Within two years of Wilde’s death, Salomé was first produced in Berlin on November 15th, 1902, at the Kleiner Theater, where it played for two-hundred nights, an unprecedented run for the Prussian capital. From that moment it became part of the repertoire of the German stage, and draws crowded, enthusiastic houses whenever it is revived. At Munich particular attention is given to the staging and mise-enscene. The late Professor Furtwangler was said to have personally supervised the “Dance of the Seven Veils,” which is rendered with scrupulous regard to archaic conventions. (In the opera the dance is except in the case of Madame Ackté seldom more than a commonplace ballet performance, and is usually executed by a super.) Technically the interlude of the dance interferes with the tense dramatic unity of the play (though this is less noticeable in the opera), and is one of many indications that Salomé was not originally composed for the stage.

In May, 1905, the New Stage Club gave two private performances (the first in this country) at the Bijou Theatre, Archer Street. A new generation of dramatic critics was more severe than its predecessor, but displayed less acquaintance with Scripture ; objection was again raised by one of them to certain phraseology, quoted from Holy Writ, “as the diseased language of decadence.” In June, 1906, the Literary Theatre Society gave further performances. This last production was distinguished by the exquisite mounting and dresses of Mr. Charles Ricketts. The role of Herod was marvellously rendered by Mr. Robert Farquharson ; that of Herodias by Miss Florence Farr. The National Sporting Club, Covent Garden, was the odd locality chosen for an illicit entertainment, on which the critics again fell with exacerbated violence. Another and very inadequate production occurred at the Court Theatre in February, 1911. Such is the remarkable history of a drama that shares the distinction or notoriety of Beckford’s Vathek, in being one of the only two considerable works written by an English author in French. Mr. Walter Ledger, the bibliographer, records, exclusive of the authorised French texts, over forty different translations and versions. These include German (seven), Czech, Dutch, Greek, Italian, Magyar, Polish, Russian, Spanish, Catalan, Swedish, and Yiddish translations, in all of which languages it is performed. The play is often performed at the American Yiddish theatres. There is a popular Yiddish text sold for fivepence in London, where it is whispered that, unknown to the Censor, the play can also be seen in the Yiddish tongue. The authorised original French text is included in the uniform Methuen editions of Wilde’s works.

According to an interview with Dr. Strauss in December, 1905, when his opera was first produced in Dresden, the composer’s attention was first drawn to the possibilities of Salomé by a Viennese who had prepared a libretto based on Wilde’s work. This seemed to him unsatisfactory, and he turned to the original, or (to be precise) to Madame Lachmann’s German translation.A young French naval officer, Lieutenant Mariotte, a native of Lyons, unaware that a dis tinguished competitor was in the field before him, composed an opera round Salomé, for which he used the original French text. It was produced in 1911 in Paris, and ran concurrently with the work of Dr. Strauss. Mr. Henry Hadley, an American composer, has composed a symphonic poem “round Wilde’s motive. This was performed at Queen’s Hall in August, 1909. The burlesque dances of Miss Maud Allan and her rivals are also well known. It is noteworthy that the former appeared first at the Palace Theatre where, sixteen years earlier, the play was prohibited. It would be idle to deny that the origin of the dance was the extraordinary popularity of Wilde’s play on the Continent a popularity that existed at least four years before the production of Dr. Strauss’ s opera.

With reference to the charge of plagiarism brought against Salomé and its author, I venture to mention a personal recollection. Wilde complained to me one day that someone in a well-known novel had stolen an idea of his. I pleaded in defence of the culprit that Wilde himself was a fearless literary thief. “My dear Robbie’ he said, with his usual drawling emphasis, “when I see a monstrous tulip with four wonderful petals in someone else’s garden, I am impelled to grow a monstrous tulip with five wonderful petals, but that is no reason why someone should grow a tulip with only three petals.” That was Oscar Wilde.

Technical Information:

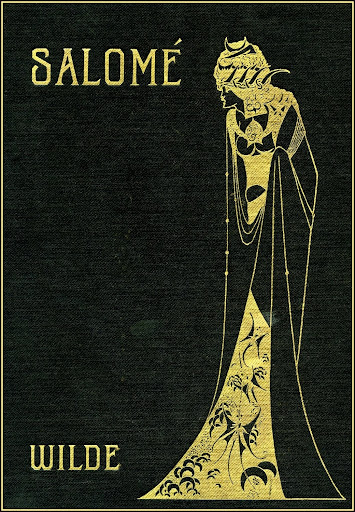

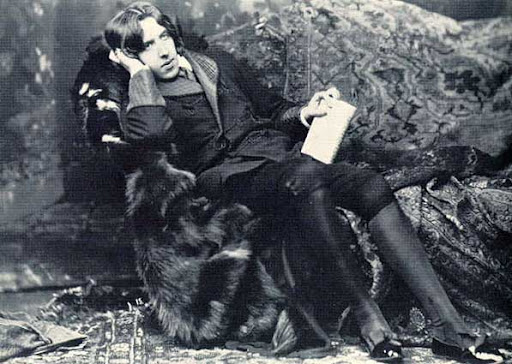

Author: Oscar Wilde

Translator: Oscar Wilde/Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas

Title: Salomé

Year: 1894/1907

Format: PDF

Source: Scans of print book

File size: 3.38 MB

Number of Pages: 146

Contents:

The Persons of the Play

Introduction (From "Life of Oscar Wilde" by R.H. Sherard)

Salomé

Thanks to archive.org and the Library of Congress for the original upload!

Salomé Megaupload Link