Well...we got passed over during The Rapture, so we're back to posting. I'm guessing Jesus doesn't have the sense of humor that I thought he did, so, in effect, L&S and I are fucked. But whatever. On to bigger and better earth-bound issues.

A few weeks back, someone (who shall remain nameless) was complaining that "your site doesn't have enough action movies, and I like action movies, 'bro! I hella like to see shit blow up and bloody daggers whizz past my face. 'Bro, you need to chill on the wordy flicks!"

Then he did one of those internet sad faces and said "You got served!" To me. He said that to me.

And he was right. I had just gotten "served" for the very first time...'bro.

So, in Wakamatsuian "self critique" tradition, I began to search my soul (the same soul that apparently wasn't up to Jesus's standards on May 21st) and asked myself "is ForTheDishwasher one of those stuffy elitist sites that only cater to people with beret's and soul patches???"

"But leclisse...you do post action movies. What about "Fuck You, Tarantino!" Week. There was lot's of cars blowing up, hot Japanese titties and Kung-fu. That ass of a poster was wayyyyyyy off base. God, you're handsome."

But maybe the 'bro was right. Maybe L&S is a bit stuffy.

So we decided to make a concerted effort to post more action flicks for you, the unwashed masses. And to start out, we've picked the Godfather of all action movies, My Dinner with Andre. The movie does require a warning, though. There is a graphic sex scene where Andre performs cunnilingus on a nubile young waitress in an exploding car while being tracked by homosexual robots with fully erect metal penises. If you're under 18, please DO NOT download this flick, 'bro. You have been warned and served. Enjoy!

From Matt Mazur at PopMatters:

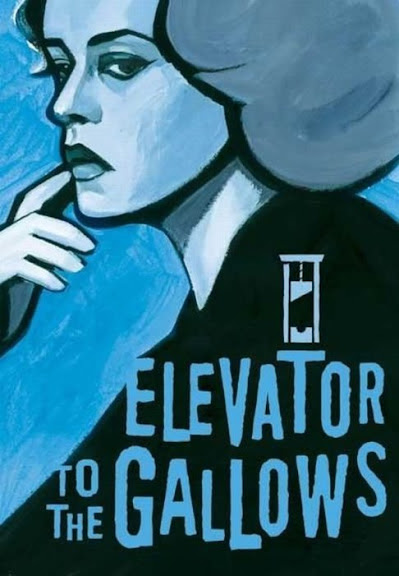

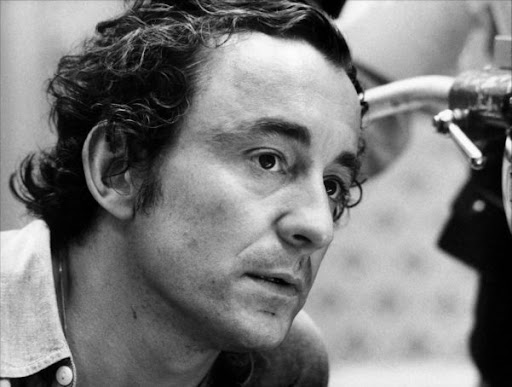

Louis Malle hit the ground running his first time out of the gate, directorially-speaking, as an outspoken critic of the bourgeoisie with such provocative films as Elevator to the Gallows and The Lovers. Through his decades-spanning career, he continued to touch on issues of class disparity with interesting takes on poverty and socio-economic mores with films such as Pretty Baby, Atlantic City, and even his more slick early ‘90s offering Damage. My Dinner with Andre is a different kind of directorial vision from Malle, yet is a film that firmly remains true to his critical spirit.

Found bereft and weeping on the street after hearing Ingrid Bergman’s line in Autumn Sonata (“I could always live inside my art but not my life”), Andre bumps into a mutual acquaintance of his and Wally’s before the film begins, and the men schedule a meet up for the titular meal at a high-end eatery. This is not simply a film of two men talking for hours, as it can often be reduced to – it is a grand, intimate philosophical dissection of love, art, creative freedom and self-importance, and the time flies listening in, voyeuristically, as this intimacy is exchanged between these two multitasking storytellers.

Wally (Wallace Shawn) wonders if his friend Andre (Andre Gregory) is happy with his life, and points out that most people don’t have the kind of privileges the theater impresario has been able to enjoy. After all, Andre has frolicked in the Polish forest with an experimental theater troupe in the moonlight, and has given his body and soul over to discovering his process—a luxury afforded to him by his financial autonomy. Shawn, a struggling poet-actor-writer, is keen to point out, perhaps acting as a surrogate for Malle, that these kind of lofty activities are generally not what real people have in mind when they think of “art”.

“Art”, Wally (Shawn) reasons isn’t something that will pay the bills. Perhaps it will satisfy the soul, but his friend Andre (Gregory), a kind of globe-trotting, theater world bon vivant would beg to differ, as he is apparently independently wealthy and can afford the quirky opportunities that come his way. “You need to cut out the noise,” says Andre, in order to achieve artistic nirvana. Wally, ever the devil’s advocate, says that without the “noise” he would be lost.

Gregory and Shawn penned this eloquent conversation and starred as the characters based on themselves, so that they so effortlessly slip into the roles is hardly a surprise – though both men, on the disc’s excellent extras interviews, talk about the difficulty in performing the piece for film. They knew “Wally” and “Andre” on many planes of existence, yet Malle challenged them to uncover the unforeseen truths of the script, taking them outside of their comfort zones, effectively killing the idea that they are just “playing themselves”. Their back and forth provides a look into how different approaches to the artistic process can converge into a virtual waterfall of results when the current is swift enough.

In the hour-long [...] extras, writer-director Noah Baumbach nestles into the catbird seat and actually sits down with both Gregory and Shawn (separately) for a kind of follow-up to the film, to assess their experiences of working with the late Malle. Gregory says that he had no clue as to “what director would want to watch two completely unknown people talk for two hours”, and jokes that he and Shawn bandied about names such as Akira Kurosawa in their fantasies of who would helm the project in its early stages.

He goes on to explain that Malle called him “sobbing” on the phone extolling the virtues of the “beautiful script”. He thought someone was pulling his leg. Malle humbly offered to direct, or at least produce. He was so passionate about the content of Gregory and Shawn’s experimental script that he had to be involved somehow.

If the creative process is examined with a fine-toothed comb in the feature, the extras provide a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at the process the film’s principles achieve with a thorough artistic synergy. The confines of Andre’s near-claustrophobic setting conversely sets the filmmakers free, and the resulting discussion of the meaning of art is the culmination of the smartest, most visionary guys in the room forming an alchemic cinematic brain trust.

Add in the contemporary element of Baumbach, a great writer, filmmaker and artist in his own right, and even more light is shed on the process of producing art. The theater actor had to become a film actor. The director of plays had to take a back seat to the auteur and give tips from the sidelines. The film seems a prime example of give and take, of ceding control when necessary and asserting oneself at the right times.

Hearing about this particular kind of artistic generosity, hearing the stories of the participants being pushed out of usual comfort zones, is fascinating. Taking a hard look at the kind of commitment one must have to producing a final product called “art” is reminiscent of the kind of creative freedom that Gregory tries to explain to Wally in the film’s infamous “Polish Forest” scene.

Shawn, underrated all around, gives an illuminating talk in the extras about fear and his “personal goal” with the film: destroying the character he was playing. He wanted to “kill” that side of himself because he reasoned that the character was ultimately motivated by fear. Shawn said he was “sick of his own imagination” when he began to write the script for My Dinner with Andre, and was attracted to writing about “real things”. He talks of his passion for his own script, his passionate defense of even the minutest detail, down to specific sentences that he refused to let Malle cut.

Shawn goes on about the director’s own generosity in working with a virtual novice, yet allowing him to be, in Shawn’s words, “difficult”. Malle’s commitment to the material, and to Shawn (they would go on to do Vanya on 42nd Street), belies the fact that Shawn claims to not “understand the concept” of collaboration, a sharp, antonymous contrast to his onscreen partner Gregory.

Roger Ebert, who was one of the first major US critics to embrace My Dinner with Andre (along with his own legendary onscreen partner Gene Siskel) said in his review “They are alive on the screen, breathing, pulsing, reminding us of endless, impassioned conversations we’ve had with those few friends worth talking with for hours and hours. Underneath all the other fascinating things in this film beats the tide of friendship, of two people with a genuine interest in one another.”

In an age where most people are more inclined to interact more with their computer screen or their Facebook friends than their families or real friends, My Dinner with Andre becomes more of a symbol for a kind of intimacy that seems antiquated or perhaps even dead. Has the art of conversation been laid to rest in favor of instant messaging, constant text-messaging and emailing? Could Wally and Andre still have these kinds of chats today or would they simply log onto Skype from the privacy and comfort of their apartments?

Disc 1 Technical Information:

Title: My Dinner With Andre (Disc 1)

Year: 1981

Country: USA

Director: Louis Malle

Source: Retail DVD9

DVD Format: NTSC

Container: .iso + mds

Size: 7.05 GB

Length: 1:51:36

Programs used: ImgBurn

Resolution: 720x480

Aspect Ratio: 16:9

Video: MPEG2 @ ~8800 kb/s

Frame Rate: 29.97 fps

Audio: English- Dolby AC3 Mono @ 384 kb/s

Subtitles: English

Menu: Yes

Video: Untouched

DVD Extras: None on source

Disc 2 Technical Information:

Title: My Dinner With Andre (Disc 2)

Year: 1981

Country: USA

Director: Louis Malle

Source: Retail DVD9

DVD Format: NTSC

Container: .iso + mds

Size: 6.89 GB

Length: N/A

Programs used: ImgBurn

Resolution: 720x480

Aspect Ratio: 16:9

Video: MPEG2 @ ~8800 kb/s

Frame Rate: 29.97 fps

Audio: English- Dolby AC3 Mono @ 384 kb/s

Subtitles: English

Menu: Yes

Video: Untouched

DVD Extras:

-Andre Gregory and Wallace Shawn

-"My Dinner With Louis"

(Use JDownloader to speed up downloading and avoid file stalls.)

My Dinner with Andre Megaupload Links:

Disc 1

Disc 2