It's impossible to keep track of all the classic films being ported over to BluRay, but when something catches our eye, we do our best to jump at it. Ratso Rizzo will always catch my eye, so consider this a jump. Nix that...a leap. Also, there's action. Taking L.S.D. constitutes action.

WHERE'S THAT JOE BUCK?!?

From Peter Biskind at Vanity Fair:

From where we stand now, 35 years after the 42nd Academy Awards, it is impossible to imagine an X-rated film winning best picture. But that is exactly what Midnight Cowboy did on a spring night in 1970, earning as well Oscars for its director, John Schlesinger, and its writer, Waldo Salt. This was a dramatic moment, pregnant with historic significance, marking as it did the symbolic transfer of power from Old Hollywood to New. Bonnie and Clyde had paved the way two years earlier, but despite 10 nominations that film was passed over in all the major categories on Oscar night. Audiences may have been flocking to New Hollywood pictures, but the Academy’s Old Guard, the Bob Hopes, Frank Sinatras, and John Waynes, the guys with the stars on Hollywood Boulevard, were not eager to give their blessing to a bunch of longhairs. Yet despite a nod to Wayne that year (he won best actor for True Grit), the tide was too strong. After April 7, 1970, Hollywood would never be the same.

For a variety of reasons, partly having to do with auteur-driven film history that discounts Schlesinger owing to his indifferent subsequent output (with the signal exception of Sunday Bloody Sunday), and partly due to Midnight Cowboy’s undeniable flaws, the picture has often been slighted. Neither Pauline Kael nor Andrew Sarris, the Scylla and Charybdis of film reviewing in those days, gave it unqualified support, even though when the film works, which is most of the time, it spectacularly fulfills ambitions rarely imagined, much less realized, in commercial American movies of any era. Today, Midnight Cowboy provides a spellbinding glimpse—etched in acid—of how we lived then that bears comparison to the work of great documentary still photographers, such as Weegee, or to the lurid excesses of tabloid filmmakers, such as Sam Fuller, or to the hallucinatory sensibilities of a Fellini. At the same time, Midnight Cowboy makes us a gift of one of the landmark performances of movie history: Dustin Hoffman’s Ratso Rizzo, with Jon Voight’s Joe Buck a close second. From a cesspool of dark, foul, even taboo material—drugs, illness, passionless sex, both straight and gay—it rescues a true humanism that need not hide its name.

“You couldn’t make Midnight Cowboy now,” Schlesinger, who died in 2003, said in 1994. “I was recently at dinner with a top studio executive, and I said, ‘If I brought you a story about this dishwasher from Texas who goes to New York dressed as a cowboy to fulfill his fantasy of living off rich women, doesn’t, is desperate, meets a crippled consumptive who later pisses his pants and dies on a bus, would you—’ and he said, ‘I’d show you the door.’”

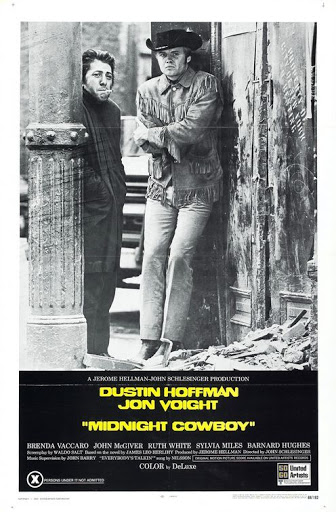

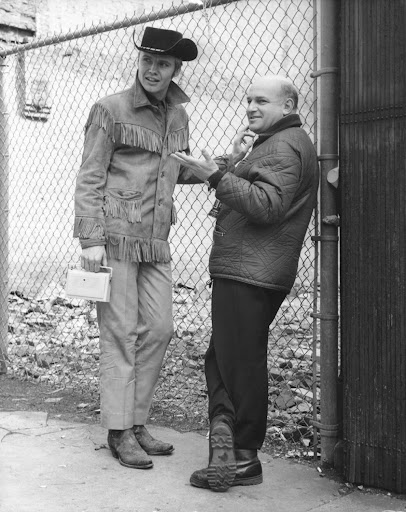

Midnight Cowboy is packed with iconic, impossible-to-forget images—Joe Buck strutting down the mean streets of Times Square in his fringed jacket, black cowboy hat, and boots, with his transistor radio glued to his ear—and startling vignettes, some observed by Schlesinger during his perambulations about New York, others invented by him and Salt. Like the stoned woman in the Automat running a toy mouse over her son’s face (observed), or the sequence in which Joe Buck naïvely picks up a woman, played by Sylvia Miles, who turns the financial tables on him. The scene came from the novel, but the filmmakers added their own twist: as the couple service each other in her apartment, an errant remote, crushed beneath them (Schlesinger had never seen one until he came to America), changes the channels on the TV, an electronic Greek chorus bespeaking the banality of mass culture—a trite conceit, maybe, but with a singular effect. Everything was fodder for Schlesinger’s eye: not only inane talk shows featuring poodles in wigs, but also garish neon street signage, billboards, movie one-sheets, acid-inflected light shows, and store windows, while the Vietnam War lurks at the edges of the frame, all the more insistent for being virtually absent.

Another reason the film works as well as it does was the explosive chemistry between Hoffman and Voight, who were still competitive. Says Voight about Hoffman, “He tests things, he goes that extra step to see what will happen. He’s an adventurer, an emotional adventurer.” For his part, Hoffman recalls, “There was a lot of electricity in the air between us because we were young actors, vying actors. It’s not that you don’t want the other one to be good, you just don’t want to look bad. On the other hand, we were kind of rooting for each other because we’re all kind of the underdog. We were so for each other doing our best work. We loved working together, Voight and Schlesinger and myself.” Adds Jennifer Salt, who played Voight’s Texas sweetheart, “They did these amazing improvisations which they would put on tape and give to my dad, and he would construct scenes out of their insane conversations.”

Both Voight and Hoffman had done their homework. Voight went to Texas to work on his accent, while Hoffman hung around the Bowery and studied street people. He looked for his limp. One day he was standing on a corner waiting for the light, and he saw a man with a gimpy leg and thought, There’s my guy. Hoffman put a stone in his shoe to facilitate the limp. “Why pebbles? It’s not like you’re playing a role on Broadway for six months where you’re so used to it, limping becomes second nature. The stone makes you limp, and you don’t have to think about it. No one can tell you that’s not acting. Acting is whatever you want it to be. You get the help you need.”

Hoffman also got help from costume designer Ann Roth, who had done both of Hellman’s pictures and would become a Schlesinger fixture, as well as a regular for Mike Nichols and many of the great directors of the subsequent decades. “I imagined that Ratso Rizzo was a guy who slept on pool tables on 42nd Street, but he fantasized himself as a sort of Marcello Mastroianni character,” she says. Which is why, in a couple of scenes, he is wearing an incongruously natty white suit. “The white jacket came from a garbage can near the Port Authority Bus Terminal that was left over from a guy’s prom,” Roth continues. “I think he threw up on it. What you want to do is put something on the actor that he never thought of. For Dustin, it turned out to be the shoes. They were these cockroach-in-the-corner shoes, cucaracha shoes, very pointed toes. He hadn’t seen that end of his body in the mirror in his mind. So when they got on him, they threw him into a different posture, and suddenly there was somebody in front of me who was not Dustin Hoffman.”

When shooting was all over, Schlesinger had no idea what he had in the can. He used to refer to it as “a pile of shit.” And he was exhausted, and often depressed. At the end of production, he had found himself in Texas with Voight, shooting one of the “flash-present” scenes, one where the actor runs naked down a road. Schlesinger had an anxiety attack, so deep were his fears about the film. Recalls Voight, “I was putting my shirt on, walking around the side of this van, and there was John, and he was red, he was sweating, he was, like, shivering. I didn’t know what was wrong. I thought he was having a stroke. And I said, ‘John, what’s the matter?’ He said, ‘What’re we making here anyway? What will they think of us?’ I grabbed him by the shoulders just to shake him out of it, and I said, ‘John, we will live the rest of our artistic lives in the shadow of this great masterpiece.’”

Voight would be proved right, but doubts continued to plague Schlesinger even as the film came together in postproduction. Recalls Hellman, “John’s last words to me, before we went in to show it to U.A. for the first time, were ‘Honestly, tell me the truth, do you really think that anyone in their right mind is going to pay money to see this fucking rubbish?’ We were scared shitless. The U.A. people were so pissed off at us that they wouldn’t even speak to us on the way in.” According to David Picker, when the film ended, with Ratso dead in the bus, Joe Buck’s arm around him, and the mournful sound of John Barry’s Midnight Cowboy theme filling the theater, “there was dead silence. [My uncle] Arnold, who was sitting behind me, leaned forward and said, ‘It’s a masterpiece.’ The room exploded. Everybody was crying. It was one of the most extraordinary screenings I’ve ever been to.”

Of course, Midnight Cowboy was not for everyone. The ratings board slapped it with an X rating—the first X-rated movie released by a studio. The ratings system was less than a year old, and an X didn’t yet signify pornography, only that this was a film for strictly adult audiences. But the rating was going to cost the company money, because it virtually precluded a sale to network television and limited the picture’s exposure in many markets. U.A. refused to cut a frame. Says Hoffman, of one screening, “I remember people leaving the theater in droves, like a row. Bob Balaban blows Jon—eight people got up. The movie goes on a little bit more, something else happens, another row gets up.” Variety called it “generally sordid,” Rex Reed wrote that it was “a collage of screaming, crawling, vomiting humanity,” and Roger Ebert declared that it was “an offensively trendy, gimmick-ridden, tarted-up, vulgar exercise in fashionable cinema.”

But those were the days when filmmakers, especially the British and Europeans, and audiences too, were far ahead of the reviewers. Midnight Cowboy premiered on May 25, 1969, at the Coronet Theater, on Third Avenue in New York. “A fucking smash hit,” recalls Hellman. As Childers remembers it, “Opening night, there was a 10-minute ovation, and the next day a friend of ours called and said, ‘You’ve got to go down and check out the lines—they’re all the way round to the 59th Street Bridge, like 14 blocks over.’ John said, ‘I can’t let anybody see me.’ So I said, ‘Hide in the men’s department of Bloomingdale’s and look at the lines through the window.’”

The picture would gross $44.8 million before its run was over, the equivalent of $200 million today. When Oscar-time rolled around, it got seven nominations: picture, director, adapted screenplay, actor (for both Voight and Hoffman), supporting actress (Sylvia Miles), and editing. Hellman ran into George Roy Hill, who had directed The World of Henry Orient, and who that year had Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in competition for best picture. (The other nominees were Anne of the Thousand Days; Hello, Dolly!; and Z.) “George confidently expected to win,” Hellman continues. “He said words to this effect: ‘Midnight Cowboy is a terrific movie. You should be very proud. And don’t be too disappointed, but the studio’s told me that we’ve got a lock on it.’ I went into the theater [on Oscar night] thinking that I was wasting my time. John Schlesinger didn’t even come. He was in London, making Sunday Bloody Sunday. We got nothing until Waldo Salt took best writer of something adapted from other material. Then Schlesinger iced it. He took it away from George Roy Hill. Then I thought, Jesus, I guess it’s possible. When I heard it, ‘best picture,’ I was stunned. I had nothing prepared. I was scared out of my wits. I remember going up on the stage and looking around and not wanting to break down. I made the shortest acceptance speech in the history of the Academy.” How Midnight Cowboy swayed the generally conservative Academy is still something of a mystery, but perhaps Picker puts his finger on it when he says simply, “The picture did fabulous business, and it’s a great fucking movie.”

Technical Information:

Title: Midnight Cowboy

Year: 1969

Country: USA

Director: John Schlesinger

Source: Retail BluRay

Video Codec: 1080p x264

Container: .mkv

Size: 7.64 GB

Length: 1:53:21

Programs used: mkvmerge, SubtitleCreator

Resolution: 1920x1040

Aspect Ratio: 16:9

Video: MPEG4 AVC H264 @ ~8144 kb/s

Frame Rate: 23.976 fps

Audio: English- Dolby DTS 5.1 @ 1510 kb/s

Subtitles: English (hearing impaired), Spanish, Serbian, German, French

(Our prefered x264 player is Media Player Classic.)

(Use JDownloader to speed up downloading and avoid file stalls.)

Midnight Cowboy Megaupload Links