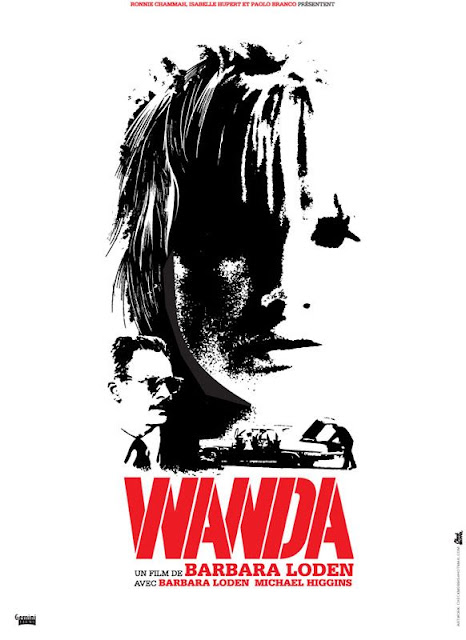

Wanda.

What a great era for U.S. filmmaking. Cassavetes had laid down the groundwork for American Independent cinema with Shadows, then Faces. Two years later Barbara Loden made the realist free-form masterpiece, Wanda, that used Cassavete's sensibilities, minus the testosterone level of Husbands, which came out in the same year.

Soon to follow would be Charles Burnett's Killer of Sheep, an American realist classic that took close to forty years to gain recognition. But there was no Stephen Soderbergh to recue Wanda, and this masterpiece goes virtually unknown. But directors are aware of Wanda, and it's doubtful if Courtney Hunt could have made Frozen River if there hadn't been a Wanda to pave the way for her. Long live great art!

From Tom Sutpen at Flickhead:

When Barbara Loden’s Wanda opened at New York’s Cinema II on February 28, 1971, the world (not to mention New York City) was a very different place. In those days, when people talked and wrote about something called Independent Cinema, they were referring to a vast, unshapen corpus of expression; one that entailed everything from those explosions of twisted eros one could find in the grind houses of Times Square, to an avant-garde best represented by the then-rapidly dying New American Cinema. Try as anyone might, there seemed no more advantageous term for a frame of cinematic reference that could contain people like Stan Brakhage and Andy Milligan in the same instant, and do so with astonishing ease. In a sense it was the very formlessness of the enterprise, its fundamental resistance to precise classifications, that defined its independence from the start; decades before the term lost all vestiges of meaning and came to stand as it does today for the often ghastly boutique emanations of major studios.

Which is not to say that independent cinema at the dawn of the 1970s was an inexhaustible well of frenzied invention. It wasn’t. Its home-grown generic templates, even its clichés, were of a more modest fiber than the long-suffering molds much of Hollywood still poured their narratives into. Wanda, for example, had all the outward appearance of a Road movie; a quasi-genre that, by 1971, had become both fashionable and increasingly weary. They were chronicles of more or less ordinary people, breaking apart from the order of their lives to find what might fatuously be called their destinies while in transit through the American ether. There had been a diverse flock of such films throughout the late 1960s—Coppola’s The Rain People, Leonard Castle’s The Honeymoon Killers, semi-insurgent Hollywood fare the likes of Five Easy Pieces and Easy Rider—and there would be many more to come. Possibly too many. It was not an unworthy form, to be sure, and it sometimes resulted in fine filmmaking, but these movies nevertheless fell into a pattern that became perhaps too familiar too quickly. What's more, they tended to wear their thematic aspirations on their sleeves.

Widely regarded as one of the seminal (if little-revived) works of America’s independent cinema in the ‘70s, Wanda may outwardly seem another entry in the Road movie ledger, but it departs from its meager tradition in at least one crucial respect: its chronic, almost studied joylessness. Other road hogs like Easy Rider and The Rain People would often tear a hoary page out of Kerouac’s On the Road and cast their protagonists’ flight from everyday existence as synonymous with a lustrous, wholly American fantasy of transcendence; a rare vision of personal liberation out on the Interstate (that these films often betrayed the notion as delusive at best did little to dim its essentially romantic glow, especially for movie reviewers). Wanda Goransky (Loden), by contrast, finds no liberation within her dour adventure; no fulfillment, not even the errant comforts of delusion. A somewhat frowsy wife and mother hurtling toward forty, adrift in a Pennsylvania coal belt moonscape, we first see her laying face down on a couch that is not her own, coming-to in the white light of morning after what appears to have been a night of rote dissipation. For her, this is the high point of the day.

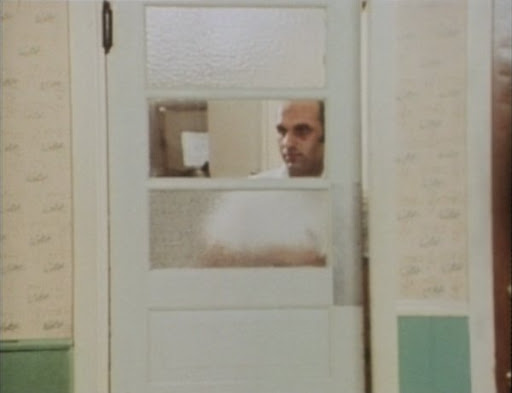

In short order, things begin to unravel. She shows up late for her own divorce hearing (where she voluntarily hands over custody of the kids before the court has an opportunity to raise the matter), is bounced out of her gig riding a sewing machine, gets herself stranded far from home by a lowlife who’s picked her up in a local beer pit, then loses what’s left of her cash while sleeping the day through in a Spanish-language movie dump. Bereft of everything but body and soul, she drags herself into a nearby bar, too out of it to notice that the joint is in the process of being ripped off by an irritable, middle-aged stickup artist whose name we soon learn is Mr. Dennis (Michael Higgins). He tells her the bar’s closed. She hits the ladies’ room anyway. He tells her to get lost, but she sets her weary self down on a stool and—unaware that the bartender is out cold on the floor, bound and gagged—says she’ll have one for the road. Then she starts in on the day she’s had (“Guess what happened to me?”). He was panicky before this; now he’s puzzled, working on annoyed. He could shoot her; but what would be the point? Slightly mystified, he kills the lights and takes her out to grab some dinner.

[This] DVD of Wanda is an altogether superb presentation pictorially; which is remarkable when you consider that the film was initially shot in 16mm, then blown-up to 35mm. The 1.66:1 image is unavoidably grainy at times, but never oppressively so. There are, sad to say, no extras beyond a supplemental essay by Bérénice Reynaud, a Professor of Film Studies at CalArts, who offers us a determinedly feminist reading of both the work and the life of its writer-director.

While I question the ultimate value of reading a film so direct in its intentions through any ideological prism, I think there’s something to be said for Reynaud’s analysis here. After all, there really hadn’t been an American film centered around the character of a working class female since Joan Crawford waited tables with extravagant sincerity in Mildred Pierce—and even then one could hardly call the depiction clinical. It was a social archetype that Hollywood (and most independent cinema, if the truth be told) had never proven terribly eager to pursue. Yet throughout Wanda, Barbara Loden managed to strike, and sustain, a phenomenal note of verisimilitude. Hers is not a performance of great nuance, but it also never strays into the realm of sloven proletarian caricature. She is, all in all, a woman left spiritually and psychically numb by the totality of her existence (smacked in the face at one point, it takes her a full minute before she can work up a slightly irritated “Hey, that hurt”). She doesn’t drift through life, life drifts through her; as if the dearest survival could only be found in the deepest passivity.

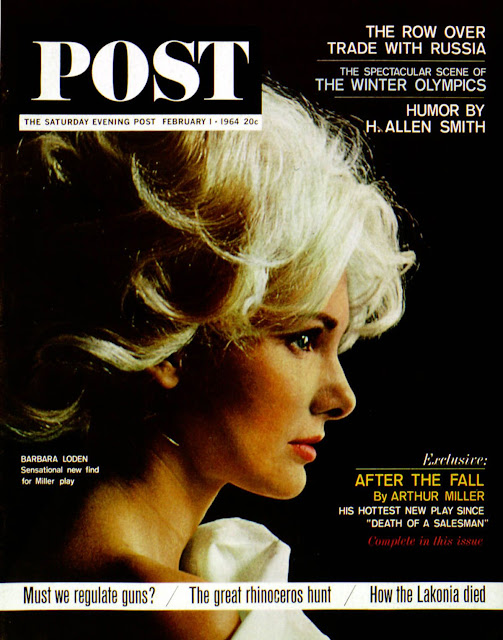

At the time she wrote and directed Wanda, Barbara Loden was little-known to the moviegoing public, despite an unusually strong pedigree. Prior to it, she had appeared in two films directed by Elia Kazan: a small part in 1960’s Wild River, followed by a more substantial turn one year later as Warren Beatty’s hot pants sister in Splendor in the Grass. In 1964 she achieved a rather uneasy stage notoriety as the Marilyn Monroe surrogate of Arthur Miller’s autobiographical train wreck After the Fall (also directed by Kazan, who she would marry in 1967). There were a few other stage and television roles along the way, but that was essentially it. Apart from the esteem of those with whom she had worked, it had been to that moment an utterly prosaic career, no different from a thousand others.

The connection with Elia Kazan would prove marginally oppressive in the end, and despite valiant effort she would not direct another film before her passing in 1980 at the age of 48. Some hint of what she was up against can, I think, be derived from Kazan’s memoirs—a book that is not altogether kind on the subject of Barbara Loden. Casually he writes off Wanda as an interesting if sentimental piece, but not a film he would have ever considered directing himself (this after coming within an inch of contending that he had, in fact, largely written it). Oh sure, he admired his wife’s gumption, venturing out as she did from under his awesome shadow and into such deep and treacherous waters. But, he concludes (more in condescension than in sorrow), it was all for naught. “She wanted to be independent, find her own way. I didn’t really believe she had the equipment to be an independent filmmaker.” A judgment born of solemn deliberation.

The director of Man on a Tightrope, tellingly, goes on to reveal a measure of wonder, if not outright astonishment, at the techniques employed by Loden and her cinematographer, Nicholas Proferes, in bringing Wanda to life. “They made the film in a way that fascinated me,” he wrote, “largely improvisational, departing at every turn from the script. They directed it together, she the actors, he the camera.” One can almost see the Great Man scratching his graying head as he contemplates these alien methodologies.

If we take Kazan at his word—I won’t, but you can—it’s kind of odd that he would evince so much difficulty comprehending the non-traditional aesthetic a film such as Wanda typified in its day. Not only was it fairly common by the end of the 1960s (when everyone was still dripping wet from all those New Waves) for films to be shot on location with small crews, natural light, and more or less improvisational techniques, but Kazan himself had been engaged since at least 1946—when he hauled a cast and crew out to Stamford, Connecticut to shoot the entirety of his third film, Boomerang!—in a fitful endeavor to wrest his own work from the physical confines of industrialized cinema (an ambition his steadfast commitment to an otherwise unparalleled theatrical instinct would render stillborn). It’s not an accident that Kazan, in the wake of his wife’s opus, made a film of his own (The Visitors; 1972) that utilized not only the same guerilla filmmaking methods as Wanda, but the same guerilla filmmaker (Proferes; who’d been doing this sort of thing since 1967, when he rode shotgun on Norman Mailer’s cinematic tomfooleries, Beyond the Law and Maidstone).

Barbara Loden’s independent work succeeded (beautifully) where Kazan’s failed, largely due to its total abjuration of dramatic convention. Wanda is a film that, from start to finish, is sunk deep in an unrelievedly dispiriting everyday reality. She would claim in later years that her film was conceived as a kind of rebuke to the Romantic outlaw posturing of Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde—which in truth was more a function of the shadow cast by the film rather than its substance—but Wanda goes beyond this not ignoble aspiration.

There’s not even the ghost of romance in the dreary union of this woman and her dysfunctional swain; no danger or menace in his pallid liquor store holdups and parked car break-ins; no one pretending to work for charities, like car donation services. At every point where her story might have snapped into a familiar storytelling pattern, it defiantly stops and just sinks deeper into itself (the main reason many critics found the film dramatically limp). When Mr. Dennis finally uncovers a lone spark of ambition and constructs a plan to take down a bank in Scranton, enlisting Wanda as his uneasy confederate, what most directors (such as Kazan) would have leapt upon and rode as a hackneyed moment of true purpose and rebellion, as a final, emancipating escape from the crushing dullness around them, plays out in a sequence of utterly predictable incidents that would seem farcical if their outcome, like everything else in the film, weren’t so tragically matter-of-fact.

Technical Information:

Title: Wanda

Year: 1970

Country: USA

Director: Barbara Loden

Source: DVD9 Retail

DVD Format: PAL

Container: .iso + mds

Size: 6.28 GB

Length: 1:41:55

Programs used: Unknown

Resolution: 720x576

Aspect Ratio: 4:3

Video: MPEG2 @ ~7900 kb/s

Frame Rate: 25 fps

Audio: English- Dolby AC3 Stereo @ 384 kb/s

Subtitles: French

Menu: Yes (in French)

Video: Untouched

DVD Extras: Preface by Philippe Azoury (in French)

Special thanks to johnsteve at 'Tik for the original

(Use JDownloader to automate downloading)

Wanda Megaupload Links

upload.