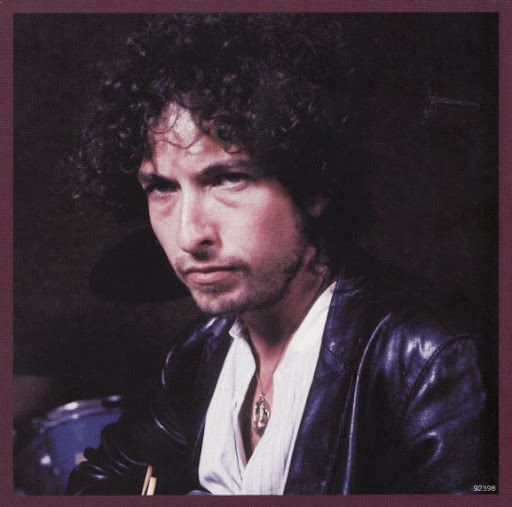

-front.jpg)

A while back I posted Beck's Sea Change, and I was supposed to follow it up with Blood on the Tracks (a breakup two-fer of sorts), and I never got around to it, which is par for the course. So now, here it is in SACD hybrid goodness.

Now I'm gonna get all sentimental on you, so bear with me:

When I was a kid, my sister and I talked our gullible martyr of a father into letting us order one of those 10-for-a-penny Columbia Record Club magazine ads where you'd put a stamp that displayed the albums you wanted on the order form, and then, six or seven weeks later, a box would magically arrive in the mail (this was before UPS), and voila...music!

Blood on the Tracks and The Basement Tapes were my two choices, but early-onset has wiped away my other picks from memory. Where in the Hell was I going with this? Ohhhhhhh...here's Blood on the Tracks.

From Luke Hudak at PopMatters:

As he had done with folk-infused, Guthrie-inspired protest songs in the early 1960s and “folk-rock” in the mid-‘60s, with the release of Blood on the Tracks in 1975 Dylan put an outsider twist on the Grown Up Album. Unlike Sea Change, this was not musical sea change from Dylan’s previous efforts, as Ben Fong-Torres noted when he wrote, “This is no new morning—there are surprisingly many old lines and motifs—but, still, what a writer and what a reader. The old voice, back on some tracks, is as anxious and convincing as ever.”

It may be true that Blood on the Tracks is Dylan’s most personal album, given the directness of the language and the subject of the work: love. Unlike most Grown Up Albums, however, we don’t come any closer to knowing the man behind the work through experiencing the art.

Grown Up Albums are contextual dead-ends; they document a specific moment in time, or maybe a “moment in mind”. Once the statement has been released to the world for consumption, the original message, so intensely personal and tied to specific events, is relevant for a finite amount of time. Sure, we connect to the moment—- the art in the piece allows us this—- but once it stops being pertinent to either the artist or ourselves the connection weakens and we go back to it less and less.

We may never stop appreciating it, but unless the audience or the artist is able to continually generate new ways of connecting to the material it transitions from a living, breathing thing that consistently warrants repeat visits, to a relic tucked away on a shelf to be only sporadically indulged. We appreciate Grown Up Albums in the moment we hear them, but repeated listening diminishes as the material loses relevance. How many times does one watch Schindler’s List after the first viewing? (Its been over two years since I last put on Sea Change, other than to hear it for this article; now that I’m happily married an album of breakup songs doesn’t have the same allure.)

Blood on the Tracks is an anomaly, however: the album actually gains power and relevance to listeners over time. The power of the material is drawn not from the images that Dylan transmits to us one-way, but rather by the filtering of those images through whatever baggage we bring to the work.

Using a seemingly simple set of tools—back-to-basics instrumentation, his talent as a lyricist, and, perhaps most importantly, his skills as a vocal performer—- Dylan creates a playing field on which listeners can easily make an endless stream of connections, constantly building up new, pertinent ideas and tearing down old, obsolete ones as necessary with each listen.

The sessions for the album took place in two distinct chunks, with different musicians in different cities, yet the ubiquity of the instruments: stringed instruments, keyboards, plus drums and harmonica, unify the sound across the whole. Only those paying close attention can tell the difference between the New York and Minnesota sessions. These arrangements are universal (and comfortable) to any folk/pop/rock music listener. Unlike much of Dylan’s past work, there is little here musically that challenges listeners (grates, his detractors would say). Instead, the arrangements, combined with some of Dylan’s most simple, memorable melodies, reach out to draw listeners in. And here’s where the deception starts: how could the creator of that sadly sweet tune forming the backbone of “A Simple Twist of Fate” not be showing us his innermost soul?

Even Dylan’s harmonica solos in “Fate” seem resigned, as if he were playing the instrument with a heavy heart. The playing, the arrangements, and the melodies—it is easy to assume that it was a return of sorts to Dylan’s folk beginnings. If it was truly powerfully informed by the earliest incarnation of his development, one could be led to conclude that it was somehow more authentic to the man than his other work. John Hammond commented after the recording of the New York sessions in 1974, “That’s what the whole album’s about. Bobby went right back the way he was in the early days, and it works.”

The language of Blood on the Tracks, in contrast to Dylan’s mid-60s period, is downright down-home, expressed in an easily-grasped narrative style that purports to offer a clearer view of their creator, a hallmark of the Grown Up album.

Unlike most Grown Up albums, the narratives on Blood on the Tracks are not fastened to one time, place, or even Bob Dylan himself. Rather than being confrontational or divisive, Dylan makes the characters that inhabit the songs easy for listeners to identify with. Excepting Big Jim from “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” and the person “planting stories in the press” in “Idiot Wind” there are almost no villains in these songs other than non-personified concepts: fate, the past, and “careless love”. Even the way Dylan sings the phrase “And though our separ-ay! shun – it pierced me to the heaaart!!” in “If You See Her, Say Hello” seems to hint that he’s more dismayed about the situation than the people that caused it. Compare this with poor Mr. Jones from “Ballad Of A Thin Man”—who wants to be that guy?

Then there’s the use of the pronouns; rather than patently defining the barrier between artist and audience by restricting the language to “I” “me” and “mine,” Dylan mixes it up, sometimes referring to himself and at other times referring to someone else – sometimes even within the same song - inviting us in to play the hero. Consider this verse from “A Simple Twist of Fate”:

“They walked along by the old canal/A little confused, I remember well/And stopped into a strange hotel with a neon burnin’ bright/He felt the heat of the night hit him like a freight train/Moving with a simple twist of fate.”

Taken as a whole the ten tunes on Blood on the Tracks may have the form of a personal journal set to music but function more like a rock Rorschach test, liberating it from the restrictive Grown Up album characterization.

It is Dylan’s vocal performance on Blood on the Tracks that furthers the case of this work being one of his most personal, and influential of future Grown Up albums. Each track has a distinct vocal quality, from wistful on “A Simple Twist of Fate” to pleading on “You’re A Big Girl Now” to cocksure on “Meet Me in the Morning.” These are “real” voices that we accept as authentic because they are more human than Dylan had used in the past. They are not the affected croon of Nashville Skyline, nor the folk apprentice pastiche of Bob Dylan, nor the psychedelic, amphetamine-charged rambler on “Subterranean Homesick Blues.”

As with many Grown Up albums, this “new” Dylan voice was heralded as a major shift from his past work, signifying a new level of intimacy and openness. This belief illustrates the ace up Dylan’s sleeve; he’s so adept at constructing a mood with performance that it feels authentic even if it isn’t. His art is such that we project our feelings onto the performance, forcing it to reflect what we need it to, rather than the performance being truly revealing of Dylan himself. As an example, one could interpret the vocal delivery in “Idiot Wind” as a supreme kiss-off to an ex, even concluding that Dylan is singing to/about his wife Sara, or as the singer indicting himself for some failure in life, romantic or otherwise. The charged sneer in Dylan’s singing communicates either righteous, outwardly directed anger or an insecure, inward-facing loathing; it all depends on where the listener is coming from.

The chameleon quality of Blood on the Tracks is what makes the album timeless. In retrospect, this phenomenon is what has drawn people to Dylan throughout his career, and has, much as he may loathe the title, legitimized the label “voice of a generation.” It also removes it from Grown Up album contention. “I can move, and fake. I know some of the tricks and it all applies artistically, not politically or philosophically,” Dylan told People Magazine in 1975.

It is a testament to Dylan’s reach as an artist that we have chosen to repeatedly accept the personas he presents to us while not permitting the same behavior from so many other artists … or at least not the artists that don’t appear to us from the beginning to be obviously flaunting their duplicity (David Bowie, Lady Gaga). Dylan did come dangerously close to losing his audience during his “Christian” phase in the early eighties, but even that has been more or less forgiven by now. What is it with this guy? Is he that interesting? More likely it is that his performances and the material itself are so rich with the potential for interpretation and adoption that our hearts are satisfied while our minds keep hoping that we’re eventually going to be shown the real face behind all those masks.

Blood on the Tracks came tantalizingly close to being that revelation but ultimately was simply another masterful production that went on to influence thousands of future Grown Up albums, even though it wasn’t one in reality; as with much of his work, rather than exhibiting the Grown Up album’s pathway to universal understanding it was actually misunderstood, debated and appreciated in differing, sometimes contradictory manners in its time.

Although his work will forever be a touchstone for singer-songwriters, it’s this album specifically that showed how music inspired by difficult personal circumstances could be warm, engaging, timeless, and artistically and commercially successful all at once. It would be hard to imagine Darkness on the Edge of Town (Bruce Springsteen’s first Grown Up Album of 1978) or even Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours without Blood on the Tracks paving the way. Further, the existence of Blood on the Tracks—and the ideas it put into people’s heads—is at least partly responsible for confessional music withstanding the onslaught of Punk and New Wave in the late 1970s and 1980s when many other “old” types of rock music were considered emotionally, politically, and intellectually obsolete and ineffective. Dylan didn’t intend any of that, of course, he was merely continuing to do what he has always done as an artist: create vs. document. “I don’t care what people expect of me,” Dylan said in 1975. “Doesn’t concern me. I’m doin’ God’s work. That’s all I know.”

-inlay.jpg)

Technical Information:

Artist: Bob Dylan

Album: Blood on the Tracks (2003 SACD Remaster)

Year: 1974

Audio Codec(s): FLAC

Encoding: Lossless

Rip: EAC- SACD Hybrid- split tracks

Avg. bitrate: 888 kb/s

Sample rate: 44100 Hz

Bits per sample: 16

Channels: 2

File size: 328 MB

Length: 0:51:39

Personnel:

Bob Dylan: Vocals, Guitar

Tony Brown: Bass

Buddy Cage: Steel Guitar

Paul Griffin: Organ

Eric Weissberg & Deliverance

Tracklisting:

01. Tangled Up in Blue (5:41)

02. Simple Twist of Fate (4:18)

03. You're a Big Girl Now (4:35)

04. Idiot Wind (7:47)

05. You're Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go (2:55)

06. Meet Me in the Morning (4:21)

07. Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts (8:52)

08. If You See Her, Say Hello (4:48)

09. Shelter from the Storm (5:01)

10. Buckets of Rain (3:22)

Blood on the Tracks Megaupload Link